Vince Lombardi, The Man

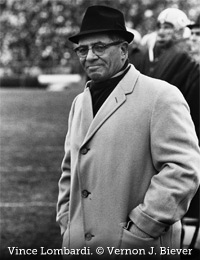

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of Vince Lombardi’s death. He died of colon cancer at Georgetown University Hospital on September 3, 1970, only eleven seasons after he had begun his incandescent run as the greatest professional football coach in history, a period during which his teams finished as champions five times. That he accomplished immortal status in barely a decade at the top is amazing enough, but there is something else about his life and death that is equally surprising. His players called him the Old Man, and that is the image the name Lombardi evokes—the quintessential father figure coach, staring at us, pushing us, with his squat build and square jaw, his professorial glasses and camel–hair coat, his gap–toothed smile and satchelful of expressions, real and mythical, about winning and the pursuit of excellence. Yet most fans who grew up watching him during the glory years of the Green Bay Packers are now older than Lombardi was when he died. The old man was gone at fifty-seven.

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of Vince Lombardi’s death. He died of colon cancer at Georgetown University Hospital on September 3, 1970, only eleven seasons after he had begun his incandescent run as the greatest professional football coach in history, a period during which his teams finished as champions five times. That he accomplished immortal status in barely a decade at the top is amazing enough, but there is something else about his life and death that is equally surprising. His players called him the Old Man, and that is the image the name Lombardi evokes—the quintessential father figure coach, staring at us, pushing us, with his squat build and square jaw, his professorial glasses and camel–hair coat, his gap–toothed smile and satchelful of expressions, real and mythical, about winning and the pursuit of excellence. Yet most fans who grew up watching him during the glory years of the Green Bay Packers are now older than Lombardi was when he died. The old man was gone at fifty-seven.

Four decades after his passing, Lombardi lives on, larger than his sport, while other great coaches of his era, from George Halas to Bear Bryant to Woody Hayes, recede with time, confined to the narrow world of football. Walk into the office of an insurance salesman in Des Moines, a college financial officer in Richmond, a hockey team president in New Jersey, and there is the Lombardi credo, framed and hanging on the wall. The Lombardi bust at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton has the shiniest nose, touched more than any other by the faithful, the sporting equivalent of rubbing St. Peter’s foot in Rome. The ambition of every player and coach in the league is to be associated with his aura, to bask in the glow of the ultimate prize awarded to the Super Bowl champions—the Lombardi Trophy. Watch any NFL promotion on television and, inevitably, there is the profile of Lombardi, the block of granite on the sidelines. Now Lombardi is even striding onto the Broadway stage in a new play written by Eric Simonson and starring Dan Lauria, who has the look, the voice, and the bona fides, a respected actor and former Marine who grew up on Long Island and once played and coached football.

The title of this book was taken from a scene in Richard Ford’s novel Independence Day in which his main character, a former sportswriter named Frank Bascombe, makes a pit stop at the Vince Lombardi Service Area at exit 16W on the New Jersey Turnpike. The “Vince,“ as Ford called it, then had a collection of Lombardi memorabilia from days when pride still mattered. Ford put the phrase inside parentheses, and I thought when I first read the passage that he intended it with a certain irony, a suspicion that he later confirmed when I asked him. That is the spirit in which I use it as well.

In examining Lombardi’s place in American life, one speculative question resounds through the decades: Could the old man prevail in today’s world? Several myths have to be dealt with before that question can be considered rationally. The first is the myth of the innocent past. The past was never innocent. The essence of human nature does not change. There were as many roustabouts, rabble-rousers, and cheaters in Lombardi’s era as there are today, and far more economic stratification and racism. The main difference is that the culture has changed, giving players more wealth, separating them more from the masses, providing them more temptations.

In examining Lombardi’s place in American life, one speculative question resounds through the decades: Could the old man prevail in today’s world? Several myths have to be dealt with before that question can be considered rationally. The first is the myth of the innocent past. The past was never innocent. The essence of human nature does not change. There were as many roustabouts, rabble-rousers, and cheaters in Lombardi’s era as there are today, and far more economic stratification and racism. The main difference is that the culture has changed, giving players more wealth, separating them more from the masses, providing them more temptations.

Next comes the myth of the most famous saying attributed to Lombardi: ”Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.“ He said it a few times, but it did not originate with him, nor did it reflect his philosophy. Another coach, Red Sanders, coined it decades before Lombardi came along, and it entered the broader public domain through a John Wayne movie in which it was uttered by a young actress, playing a tomboy daughter of a football coach, who is talking to a social worker played by Donna Reed&emdash;not exactly the most macho setting. To Lombardi, it was the pursuit of excellence that mattered most. He was often harder on his teams when they played poorly but won than when they played well and lost.

And finally there is the myth of Lombardi’s leadership methods. It was Henry Jordan, a defensive tackle for the old Packers, who uttered the oft–repeated phrase “Lombardi treats us all alike, like dogs.” Memorable, but inaccurate. Lombardi was an adept psychologist who treated each of his players differently. He rode some mercilessly but stayed away from others, depending on how they responded. He did not mind oddballs—his teams were full of them—as long as they shared his will to excel. Lombardi was a Jesuit in his football instruction, as in most other things. Like Saint Ignatius of Loyola, he believed in free will, that each man was at liberty to choose between action and inaction, good and evil, the right play and the wrong play. He made things simple for his players by taking nothing for granted, repeating the same lessons to them over and over, every day, every year. He would spend hours diagramming one play, the Packer Sweep, so that his players knew how to adjust to whatever defense the opposition might employ. The point of his repetition was a timeless idea that is as applicable in jazz and dance and writing and other art forms as in football—freedom through discipline.

All of this, Lombardi the teacher, the psychologist, the adapter, the philosopher, would serve him well in today’s world. The man and the myth are always at play in the Lombardi story, converging and separating. Many yearn for the old man out of a longing for something they fear has been irretrievably lost. Every time a player dances and points at himself after making a routine tackle, or a mediocre athlete and his agent hold out for millions, whenever it seems that individual ego has overtaken the concept of team, people wonder, mournfully, what Lombardi would say about it. Others think Lombardi represents something less romantic, a symbol of the American obsession with winning, a philosophy that if misapplied can have unfortunate consequences in sports, business, and life. The concerns on both sides are valid, but the stereotypes from which they arise are misleading. Lombardi was more complex and interesting than the myths surrounding him. These are the contradictions—the depth of a simple man, the imperfections of a perfectionist, the ambiguity of his meaning in American culture—that drove me as I researched this biography.

David Maraniss

Author, When Pride Still Mattered—A Life of Vince Lombardi

Washington, D.C.

May 2010